Lion Air disaster: just a blip in Asia’s runaway air travel boom?

- The Indonesian carrier’s crash that killed 189 people raises questions over whether Asia’s aviation sector is struggling to keep up with breakneck growth.

Asia is set for a boom in air travel, according to a range of forecasts, but the eye-popping predictions have also brought concerns about congested airports, a lack of pilots and flight safety.

Lion Air, furious at Boeing over crash blame, may cancel billions in orders

“The aviation boom in Asia is a game changer,” said Conrad Clifford, the IATA’s regional vice-president for Asia-Pacific. “We are forecasting that Asia-Pacific will see an extra 2.35 billion annual passengers by 2037, for a total market size of 3.9 billion passengers. This growth is a huge opportunity for the region’s economies and aviation but also a challenge in terms of infrastructure, human capital, regulation and investment.”

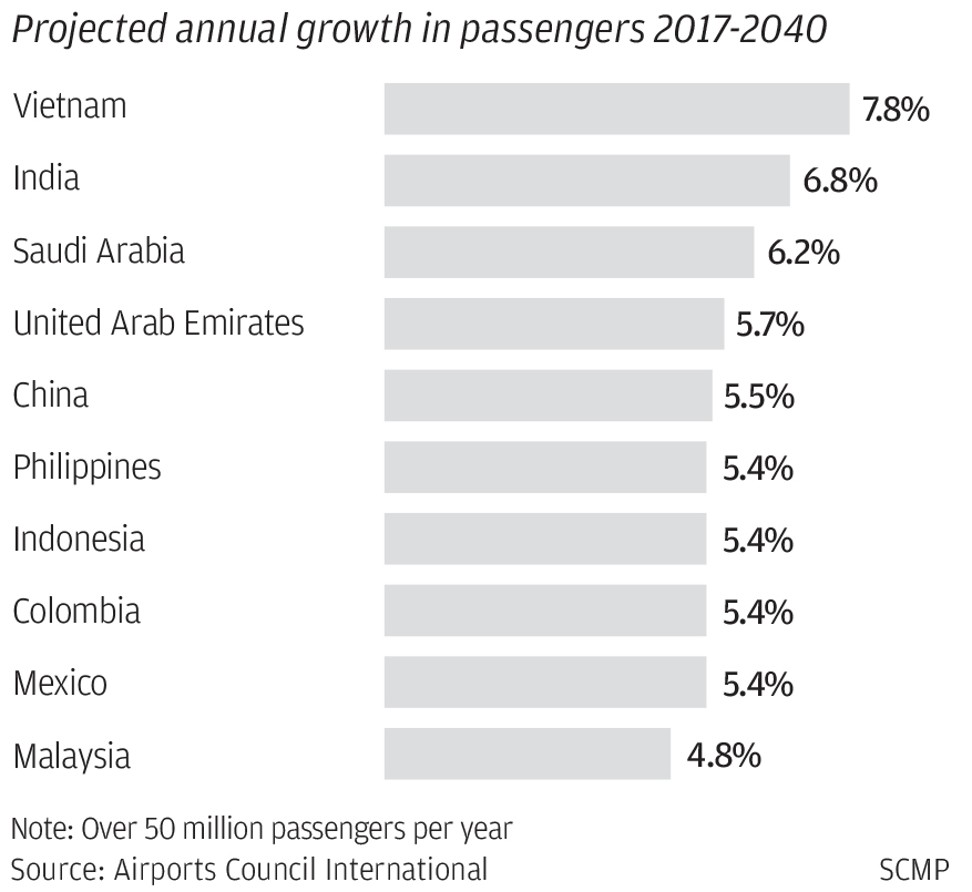

Airports Council International (ACI) predicts that by 2040 China will become the largest passenger market with just under 4 billion passengers, or about 20 per cent of all global traffic, while India will have 1.3 billion. The Asia-Pacific region, over the same time, is expected to contribute more than 42 per cent of all international air travellers.

By 2030, it is estimated that air travel in Asia will be bigger than the next two markets – North America and Europe – combined. Travel isn’t the only factor: an IATA study found that by 2035, air transport was expected to support more than 70 million jobs and nearly US$1.3 trillion in gross domestic product – compared to more than 33 million jobs and upwards of US$700 billion in GDP in 2014.

“The way that aviation goes hand-in hand with economic and social development is well understood,” said Andrew Herdman, director general of the Association of Asia-Pacific Airlines. “In Asia, that applies to large and small countries and nations in different states of development. There’s a commitment to growth here.”

India’s aviation regulator wants pilots to train in a simulator that replicates Lion Air crash

Aviation experts said the industry must overcome various challenges to capitalise on the boom. As Goh Choon Phong, the chief executive of Singapore Airlines, wrote in the 2018 IATA annual review: “Clearly, the key constraint is infrastructure.”

Infrastructure in this context mostly refers to airports, planes and the people needed to fix and fly them. The shortages, many insiders said, are acute.

“The industry in Asia is going to need literally hundreds of thousands of aviation workers over the next 20 years: pilots, flight attendants and, just as important, is what we call the MROs, the technicians in charge of maintenance, repair and overhaul,” said Matt Driskill, the editor of Asian Aviation magazine.

Driskill is hardly exaggerating: Boeing, the US aerospace giant, estimated that by 2037 the Asia-Pacific region would need 240,000 new pilots, more than half of those in China. The company’s 2018 Boeing Pilot and Technician Outlook, meanwhile, said the region would need nearly 320,000 cabin crew over the same period.

“These are the men and women who keep the plane safe, and this is one of the big concerns that people have. One of the problems is that there aren’t enough training facilities for pilots and ground crew. A whole generation is retiring, so another problem is how to get young people interested in the industry. For the MRO techs, I call it code monkeys versus grease monkeys. Everything today is run by algorithms, and young people are asking, ‘Why would I want to be an air plane mechanic?’”

The shortage of aviation workers comes at a problematic time: thousands of new planes are already on order by regional airlines. Boeing has projected that 40 per cent of its new passenger planes will be delivered to Asia, and experts estimate the same to be true for Airbus, the European aerospace conglomerate. Most of these orders, according to Driskill, will be “single-aisle planes” like the Boeing 737 and the Airbus A320.

“The global order book is heavily tilted to Asia, but where do these planes park and where do they fly?” said Brendan Sobie, the chief analyst for think tank the CAPA Centre for Aviation. “The airlines might be able to fill them up with passengers, but is there enough space in the airports and in the air to accommodate them?”

Most Asian airports, including those in Jakarta, Manila and Beijing, are operating at – or over – their original capacity, according to Sobie and other experts. Hundreds of new facilities, meanwhile, are in development or stuck in the slow, thorny process that inevitably requires some level of government approval and large amounts of capital. CAPA has estimated that some 230 new airports are being built in the Asia-Pacific region, more than half the world’s total.

“Virtually every Asian country needs airport infrastructure,” Sobie said. “Some need it more urgently and some need it in other places, like secondary cities. But the main capital cities have a situation where there is not enough growth to meet the increased demand. Bangkok’s two airports are at capacity, so they’re focusing on a third airport, and Hong Kong is a good example: growth has been slow there because there is no more space.”

Lion Air crash was so intense it tore black box apart

The pace of growth, according to Clifford, the IATA regional vice-president, has forced the industry into a race against time.

“Aircraft have been ordered but airports need to have enough slots, runways and gates to handle them,” he said. “Air traffic control needs to be enhanced to handle these flights efficiently and safely, and airport terminals need to be expanded to provide a safe, secure, efficient and pleasant experience to all these additional passengers. But there is just not enough time, space and money to triple the airport building infrastructure for this growth.”

COMPETITION, SAFETY

For an industry facing many challenges, the Lion Air disaster could not have come at a worse time. Analysts have been left to determine whether the fatal crash was a blip in an otherwise much improved safety record, or a symptom of breakneck growth and intense competition.

“One problem is that everybody and their dog wants to be the next Tony Fernandes and be the next AirAsia and make millions of dollars,” said Driskill of Asian Aviation, referring to the chief executive of Malaysia-based AirAsia, Southeast Asia’s largest low-cost carrier.

“There is this intense pressure to grow, grow, grow and, combined with a lack of skilled pilots and MRO techs, these things have led to safety problems as we have seen with Lion Air and some of the Indian carriers.”

“If you look at the profit margins, most airlines are running on about US$10 profit per passenger per flight. I heard one executive say that is basically a hamburger and a Coke away from making a loss. So when you have such thin profit margins, and the only way to make money is to keep planes in the air, there is a real incentive to fly that thing 24/7,” Driskill said.

Tom Ballantyne, the chief correspondent for Orient Aviation magazine, has covered the industry in Asia for 25 years. He urges caution when considering the recent disaster.

“The Lion Air crash reflects poorly on the industry. For many people, it’s another crash in Indonesia. But you have to recognise that it’s a single incident and the Asia-Pacific region, in fact, has an incredible safety record. In 2017, there were no accidents, and there have been real improvements: China, which once had a poor safety record, now has one of the best safety records in the world.”

Still, safety concerns from the public remain another major headache for an industry facing plenty of challenges. The Lion Air accident has intensified scrutiny of Indonesia’s aviation safety practices, and the government has called for increased oversight of the nation’s airlines.

Despite this, as Ballantyne points out, the staggering growth appears set to continue.

“It’s happening: and the number one concern in Asia is whether the infrastructure can keep up with the growing demand. At the moment it certainly is not,” he said. “Every time I write stories about the region and China or India, you almost can’t believe the numbers. But the forecasts are real, and they’re not even forecasts any more, the growth is already here.”

Alvin Lie, a former Indonesian lawmaker and aviation expert who now consults for the country’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), said the Lion Air crash had sent a clear warning to the government. He said the DGCA was already taking a look at pilots’ hours and working to digitise logbooks.

“If there is any fault in the Lion Air tragedy, the blame is on Boeing for the plane’s technical problems,” Lie said. “But another issue that deserves attention is the airlines, such as Lion Air. The number of planes they operate and the number of routes they serve – it doesn’t make sense. Sometimes they operate below the minimum number for crew.”

Lie was adamant, however, about the negligible effect he believes the Lion Air disaster will have on Indonesia’s aviation sector, which he praised as “one of the fastest growing in the world”.

“If you look at the safety record of Indonesia it has improved tremendously. In fact, in 2017 there wasn’t a single accident or fatality. The Lion Air accident doesn’t reflect on Indonesia’s air safety.” ■